Introduction

High incidence and prevalence make stroke the leading burden for societies, especially in middle and low-income countries [1]. There is no national stroke registry in Moldova. The only source of demographic data is provided by the National Bureau of Statistics, and many indicators of in-hospital stroke care became accessible after Moldova’s accession to the RES-Q platform in 2016. Thus, the National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova estimated that 3% of the population of Moldova are stroke survivors and 1 of 7 deaths is attributed to stroke [2]. The mortality rate due to cerebrovascular diseases reported in 2019, remains one of the highest in Europe with 145.7 deaths /100000 population and 56% of all stroke patients died at home [2]. According to the most recent epidemiological study, the main stroke risk factors in Moldova’s population are dyslipidemia (55%), obesity (43%), hypertension (36%), smoking (15%) and diabetes (7%) [3]. Despite the existing of a national guideline for acute stroke treatment in Moldova only a small number of patients receive adequate treatment through recanalization procedures due to reduced accessibility to the diagnostic facilities in the first hours after hospitalisation.

There are perceived discrepancies in acute stroke care between Eastern and Western European countries. They might be explained by the socio-economic determinants, as well as structural differences and peculiarities of the health care services. If this is the case, there is an urgent need to reduce these gaps and inequalities, and to improve the quality of stroke care across the Eastern European countries. In order to improve stroke care and clinical outcomes and to reduce the healthcare costs, one of the first steps forward was to establish a stroke registry. The goal was to measure and evaluate the quality and performance of stroke indicators [4].

There is lack of data on stroke care quality in Eastern European countries. Our aim was to assess the acute stroke care quality performance indicators in the Republic of Moldova, based on the RES-Q (Registry of Stroke Care Quality) data, and to compare it to some other countries of the RES-Q ESO-EAST project.

Material and methods

This is a retrospective data analysis of the patients enrolled prospectively in the RES-Q registry from 2017 to 2019.

Moldovan health care service overview and participating hospitals

The population of the Republic of Moldova is 2.6 million people with a density of 86.2 people/km2. The country is divided into 32 territorial districts. Each separate district has its own hospital, that admit rural patients. In two largest cities of the country there are municipal hospitals, where are treated patients from cities and suburbs. In the capital there are also the tertiary level centers such as republican hospitals, where are referred the most difficult patients from anywhere in the country, but also from the capital-city Chisinau.

There are 68 public hospitals in Moldova, 24 (35.3%) of which have a neurology department, and 16 of them being district hospitals. The catchment area of a district hospital covers on average 80.000 people (minimum of 50.000, maximum of 103.000), and an average area of 1.000 km2 (854 - 1545 km2), while the municipal and republican hospitals cover between 100.000 and 820.000 people on an area between 78 and 123 km2.

The participating centers’ catchment area is of 1.6 million inhabitants, representing 61% of the national coverage, with 3 hospitals fulfilling the basic Stroke Unit criteria and requirements, according to the ESO definition [5].

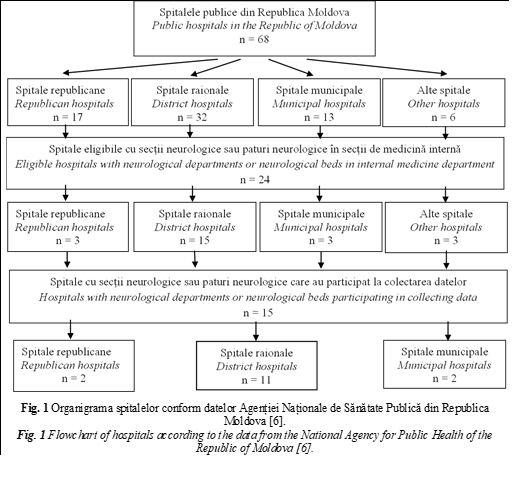

The heads of all neurological departments involved in stroke treatment were invited to initiate the RES-Q registry data collecting. Since the decision to join the RES-Q data collection process was on a voluntary basis, only fifteen hospitals from 13 territorial districts answered positively and enrolled in the initiative. The affiliation of participating hospitals is shown in Fig.1.

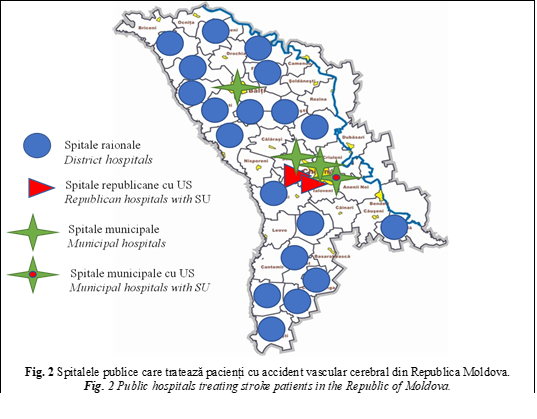

Currently, there are 47 CT scans in the whole country. Most of them (38) are concentrated in the capital city (Chisinau) and only 9 of them are installed in public hospitals, and the rest – in the private medical centers. This limits significantly the ultra-fast access to stroke therapy. Only 3 hospitals with Stroke Units (SU) exist, all located in the capital (Fig.2).

Based on CT availability the Moldovan hospitals are divided into three categories: (1) CT on a 24/7 basis, all located in the capital city, (2) hospitals with CT access within working hours only, and (3) hospitals without any CT access. In hospitals with no access to CT brain imaging was performed either at another hospital during hospital stay, or the diagnosis was made simply based on WHO stroke clinical criteria [7]. Hospitals with unlimited access to CT establish the diagnosis of stroke at site and admit the patients in either SU, Intensive Care Unit (ICU) or Neurological departments. In hospitals with partial and no-CT access patients are admitted in the ICUs, Neurological departments, and/or Internal Medicine departments.

Quality and performance metrics

The protocol, the items and the quality indicators that are included in the electronic case report forms (eCRFs) are published elsewhere [8, 9]. In brief, the following metrics were collected: demographic data (age, gender, stroke severity, and stroke type), diagnostic procedures (brain and carotid artery imaging), patient hospitalization data (hospitalization department), recanalization, and surgical treatment if applied, prevention of post-stroke pneumonia (dysphagia screening), secondary stroke prevention (medication, endovascular procedures), and patient discharge information.

RES-Q

The RES-Q platform was launched by ESO within the ESO-EAST project in 2016, in which more than 70 countries, including Moldova, are currently participating [8]. This platform provides the opportunity to register, analyze, and identify gaps in stroke quality performance at different levels. This enables countries to devise and implement measures to improve the stroke care system. The data were entered in the RES-Q online (https://qualityregistry.eu/) by each site and were subsequently centrally processed and analyzed.

Tabelul 1. Caracteristicile pacienților din Republica Moldova. Table 1. Characteristics of patients from Republic of Moldova. | |||

Variabilele Variables | CT nelimitat non-stop CT n=890 | CT parțial partial CT n=365 | fără CT no-CT n=405 |

Factori sociodemografici Sociodemographic |

| ||

Vîrsta medie, ani, (IIC) Median age, y, (IQR) | 67 (60-75) | 68 (61-76) | 68 (62-76) |

Femei, %, (95% IÎ) Female, %, (95% CI) | 48% (45-52%) | 53% ([47-58%) | 53% (48-58%) |

Metode de diagnostic Diagnostic methods |

| ||

CT efectuate, %, (95% IÎ) CT performed, %, (95% CI) | 98% (97-99%) | 68% (62-75%) | 34% (27-42%) |

CT efectuate timp de o oră, %, (95% IÎ) CT performed during 1h, %, (95% CI) | 78% (75-81%) | 9% (5-14%) | 3% (0-10%) |

Efectuarea imagisticii arterei carotide, (95% IÎ) Carotid artery imaging performed, %, (95% CI) | 63% (59-67%) | 10% (6-14%) | 5% (2-10%) |

Factorii atribuiți ictusului Stroke related factors |

| ||

Scor NIHSS initial, media, (IIC) Baseline NIHSS, median, (IQR) | 9 (5-14) | 13 [7-19] | 9 [6-15] |

Ictus nespecificat, %, (95% IÎ) Unspecified stroke, %, (95% CI) | 2% (1-3%) | 32% (23-41%) | 66% (61-71%) |

Procesul de îngrijiri, Process of care |

| ||

Pacienți spitalizați în US / UTI, %, (95% IÎ) Patients admitted in SU / ICU, %, (95% CI) | 39% (36-42%) | 35% (30-40%) | 36% (31-41%) |

Pacienți spitalizați în secția de terapie, %, (95% IÎ) Patients admitted to Internal medicine department, %, (95% CI) | 1% (0-2%) | 9% (6-14%) | 11% (7-15%) |

rtPA IV administrat pacienților cu II, %, (95% IÎ) IV rtPA performed in IS patients, %, (95% CI) | 3% (2%-4%) | - | - |

Screeningul disfagiei efectuat, %, (95% IÎ) Dysphagia screening performed, %, (95% CI) | 19% (16-21%) | 29% (23-35%) | 69 % (61-76%) |

Profilaxia secundară a ictusului Secondary stroke prevention |

| ||

Prescrierea de anticoagulante pacienților cu II, %, (95% IÎ) Anticoagulants prescribed in AF patients with IS, %, (95% CI) | 50% (44-56%) | 22% (12-36%) | 38% (26-52%) |

Prescrierea de antiplachetare pacienților cu II, %, (95% IÎ) Antiplatelets for IS patients prescribed, %, (95% CI) | 92% (88-95%) | 91% (85-95%) | 96% (89-99%) |

Prescrierea de statine, %, (95% IÎ) Statins prescribed, %, (95% CI) | 42% (38-46%) | 47% (40-53%) | 40% (33-48%) |

Informație la externare Discharge information |

| ||

Mortalitate intraspitalicească pe motiv de ictus, %, (95% IÎ) In-hospital stroke mortality, %, (95% CI) | 20% (18-23%) | 18% (14-22%) | 8% (6-11%) |

Pacienți externați la domiciliu, %, (95% IÎ) Patients discharged home, %, (95% CI) | 68% (64-71%) | 77% (72-81%) | 78% (74-82%) |

Pacienți externați în centre de recuperare, %, (95% IÎ) Patients discharged to rehabilitation center, %, (95% CI) | 10% (8-12%) | 1% (0-2%) | 8% (5-11%) |

Notă: IIC – interval intercuartil; IÎ – interval de încredere; US – Unitate Stroke; UTI – Unitate Terapie Intensivă; II – ictus ischemic; FA – fibrilație atrială. Note: IQR - interquartile range; CI - confidence interval; SU – Stroke Unit; ICU – Intensive Care Unit; IS – ischemic stroke; AF - atrial fibrillation. | |||

Data collection

The data were collected during one month every year, between 2017 and 2019. Each hospital collected at least 30 consecutive patients with ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Every year, before the start of the data collection, all responsible staff were familiarized with the RES-Q protocol and trained accordingly to accurately obtain and fill-in the quality indicators in the registry forms.

Selection of countries for comparison

Moldovan data were compared to the data of Romania, Lithuania, and Georgia because of the similarities of country size, the number of inhabitants or geographical proximity.

Five out of eleven hospitals in Lithuania that treat stroke patients participated in the study, all of them being comprehensive centers with Stroke Unit, brain CT 24/7, MRI available during working hours, IV thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy available 24/7. Romania included the data of 25 % of stroke patients, admitted in 17 out of 65 hospitals (12 of them with SU and 4 - with the possibility to perform thrombectomy). Georgia presented the data of patients hospitalized in 5 out of 200 centers admitting stroke patients (all 5 have CT 24/7 and 3 of them provide recanalization treatment by thrombolysis and thrombectomy).

The data were collected during the same period of time (2017-2019). All participating countries followed the same procedure of data collection and fulfill the protocols for the RES-Q registry.

Statistics

Continuous and categorical variables are reported as medians with interquartile range or frequencies with percentages. 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for all proportions using binomial exact calculation. Statistical calculations of all medians, interquartile ranges and frequencies were conducted using custom SQL (structured query language) scripts directly querying RES-Q database for patients discharged from 1.1.2017 till 30.6.2019.

Furthermore, Moldova hospitals were divided into three groups based on CT availability (non-stop CT, partial CT, non-CT) and all metrics were analyzed for each group separately (shown in Table 1) and for all hospitals together (shown in Table 2).

Tabel 2. Datele comparative ale pacienților înrolați. Table 2. Comparative data of the enrolled patients. | ||||

Variabilele Variables | Moldova Moldova n=1660 | România Romania n=4265 | Lituania Lithuania n=889 | Georgia# Georgia# n=577 |

Factori sociodemografici Sociodemographic |

| |||

Vârsta medie, ani, (IIC) Median age, y, (IQR) | 68 (61-75) | 72 (64-80) | 73 (63-81) | 70 (62-78) |

Femei, %, (95% IÎ) Female, %, (95% CI) | 51% (48-53%) | 50% (48-51%) | 52% (49-56%) | 47% (36-45%) |

Factori atribuiți ictusului Stroke related factors |

| |||

Scor NIHSS initial, media, (IIC) Baseline NIHSS, median, (IQR) | 10 (5-16) | 7 (4-15) | 9 (6-15) | 12 (8-19) |

Metode de diagnostic Diagnostic methods |

| |||

CT efectuate, %, (95% IÎ) CT performed, %, (95% CI) | 81% (79-84%) | 98% (98-99%) | 99% (97-99%) | 99% (97-100%) |

CT efectuate timp de 1 oră, (95% IÎ) CT performed during 1h, %,(95% CI) | 60% (56-63%) | 77% (76-79%) | 74% (71-77%) | 94% (91-96%) |

Procesul de îngrijiri Process of care |

| |||

Pacienți spitalizați în US / UTI, %, (95% IÎ) Patients admitted to SU/ICU, %, (95% CI) | 38% (35-40%) | 24% (22-25%) | 61% (58-64%) | 88% (85-90%) |

Pacienți spitalizați în secția de terapie, (95% IÎ) Patients admitted to the internal medicine department, %, (95% CI) | 4% (3-6%) | - | - | 2% (1-4%) |

rtPA IV administrat pacienților cu II, %, (95% IÎ) IV rtPA performed in IS patients, %, (95% CI) | 3% (2-4%) | 6% (5-7%) | 26% (23-30%) | 1% (0-3%) |

Screeningul disfagiei efectuat, %, (95% IÎ) Dysphagia screening performed, %, (95% CI) | 29% (27-32%) | 62% (61-64%) | 39% (36-42%) | 88% (85-91%) |

Profilaxia secundară a ictusului Secondary stroke prevention |

| |||

Prescrierea de anticoagulante pacienților cu II, %, (95% IÎ) Anticoagulants prescribed to AF patients with IS, %, (95% CI) | 44% (39-49%) | 82% (79-84%) | 82% (77-86%) | 84% (78-89%) |

Prescrierea de antiplachetare pacienților cu II, %, (95% IÎ) Antiplatelets for IS prescribed, %, (95% CI) | 91% (88-94%) | 94% (93-95%) | 93% (89-97%) | 94% (91-96%) |

Prescrierea de statine, %, (95% IÎ) Statins prescribed, %, (95% CI) | 42% (39-45%) | 78% (76-79%) | 51% (48-55) | 85% (82-88) |

Informație la externare Discharge information |

| |||

Mortalitate intraspitalicească pe motiv de ictus, %, (95% IÎ) In-hospital stroke mortality, %, (95% CI) | 17% (15-19%) | 15% (14-16%) | 8% (6-10%) | 2% (1-4%) |

Notă: IIC – interval intercuartil; IÎ – interval de încredere; US – Unitate Stroke; UTI – Unitate Terapie Intensivă; II – ictus ischemic; FA – fibrilație atrială. # Notă: datele din Georgia include doar cifrele pacienților cu ictus spitalizați în unitățile Stroke și secțiile de neurologie. Din acest motiv mortalitatea intraspitalicească demonstrează indicatori neobișnuiți de mici. Atunci când sunt adăugate cazurile de ictus din unitățile de terapie intensive generale ale spitalelor participante în perioadele de timp relevante mortalitatea totală prin ictus intraspitalicesc se ridică la 12%. Note: IQR - interquartile range, CI - confidence interval, SU – Stroke Unit, ICU – Intensive Care Unit, IS – ischemic stroke, AF – atrial fibrillation. # Note that the data from Georgia includes only figures for stroke patients admitted to stroke units and neurological wards. That is why the in-hospital mortality rate shown is untypically low. By adding stroke cases admitted to the general intensive care units of the participating hospitals in the relevant time period, the actual total in-hospital mortality figure increases to 12%. | ||||

Informed consent was not needed because this was an anonymous retrospective analysis of existing data that were obtained in routine diagnostic procedures. The study was approved by the National Committee for Ethical Expertise of Clinical Trial of the Republic of Moldova. In Romania and Georgia, the study was approved by local ethical committees in participating hospitals.

Results

1660 consecutive patients with acute ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, over the age of 18 from the Republic of Moldova were included in the study.

CT was available non-stop in 3 hospitals; partial availability of brain imaging was in 4 hospitals and 8 hospitals had no CT. Quality indicators stratified by the availability of CT is shown in Table 1.

Median age of patients and gender distribution were similar in all groups of hospitals. In the Republic of Moldova hospitals with partial or no brain imaging have as well poorer diagnostic and neurorehabilitation facilities. As is shown in Table.1 diagnostic methods applied to stroke patients e.g., CTs and carotid artery imaging were significantly worse in non-CT and partial-CT access hospitals. Distribution by sub-types of strokes was the following: 66% ischemic stroke, 15% hemorrhagic stroke and in 19% of patients the type of stroke remained unclassified because of the lack of brain imaging. Most of these cases come from hospitals without CT access (66%).

None of the patients in the rural areas (hospitals without or partial access to CT scan) received IV thrombolysis. The majority of patients received antiplatelets (91-96%) despite the fact that CT was performed only in 34% (non-CT) and 68% (partial CT access) of patients in these hospitals. The patient admission in SU or ICU was almost identical (35-39%) irrespective of the CT scan access. In district hospitals, without SU and limited or no CT access, a significant amount of stroke patients (9% - in partial CT and 11% in no-CT hospitals) were hospitalized in the departments of internal medicine (Table 1). After discharge the percentage of patients referred to neuro-rehab departments were low in all groups, mostly in non- and partial CT access hospitals.

The in-hospital quality indicators of the patients from Republic of Moldova compared with those from the other three ESO-EAST project countries are shown in Table 2.

The demographic data showed quasi similar figures in all countries. The percentage of brain imaging diagnosis (81%) in Moldovan hospitals was the lowest one. Thus, there were 3% of patients, that benefited from the recanalization procedures in Moldova, 6% - in Romania and 26% in Lithuania. Dysphagia screening was applied in 29% of Moldovan stroke patients. The rate of anticoagulant administration in ischemic stroke patients with AF in Moldova was 44% (Table 2). Post-stroke statin prescription was the same regarding the access to CT scan (Table 1).

The highest mortality rate was noticed in the hospitals with unlimited access to CT (20%), compared to the hospitals without direct access (8%) or limited access to brain imaging (18%) (shown in Table 1).

Discussion

The introduction of mandatory health insurance in 2004 is one of the major reforms of health care sector of the Republic of Moldova. This ensured the access of the population to the modern and more expensive methods of diagnosis and treatment, including those related to the stroke management. Two National Programs focused on risk factors and primary stroke prevention were initiated and realised in the last decade. The most recent efforts of the authorities to implement thrombolysis and thrombectomy in Moldovan hospitals have led to the approval of the additional separate financing of these expensive services by the National Insurance Company. Thus, stroke treatment became more attractive for regional hospitals. Regretfully though, the lack of a National Stroke registry made the analysis of in-hospital quality indicators impossible.

This is the first study conducted in the Republic of Moldova in which quality indicators of stroke management were collected, quantified, and analyzed.

Our data showed severe disparities between Moldovan hospitals. The suburban and rural areas are the most disadvantaged and the data are consistent with those of other studies [10-13]. A stroke care system of only three well-equipped stroke units and CT facilities in the country, all located in the capital, is insufficient and inadequate. Based on the number of inhabitants, 12 fully equipped Stroke Units are mandatory for the provision of the high-standard medical care at the country level for all stroke patients [14]. The analyzed data proved that the hospitals with SU and unlimited access to CT facilities performed better compared to those without access to brain imaging. Unfortunately, this is a common situation for low- and middle-income countries [15].

Although the percent of CT performed showed worse results compared to other countries, the data from the hospitals with unlimited access to CT did not reveal any differences when compared to those from Romania, Lithuania, Georgia, and even German registries (99.4%) [16].

The analyzed data revealed that the patients in the Republic of Moldova were younger than those of other ESO-EAST project countries (Romania, Lithuania) and compared with other western European countries such as Germany, Netherlands, and Spain, (68 versus 72 y/o.) [16-18].

The analysis of collected data showed that the indicators related to the accuracy of the diagnosis, use of vascular recanalization treatment and prescription of anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation, were significantly better in patients treated in hospitals with unlimited CT scan access albeit some of them are far from the current international guidelines recommendations [19]. One of the worse indicators for Moldova was the use of IV thrombolysis (rtPA) treatment for acute ischemic stroke compared to other RES-Q countries such as Romania or Lithuania, and registry data from the Netherlands - 22% [17], Germany - 13.6%, Sweden - 13.3% [16], Spain - 15% [20] and Canada - 11% [21]. The IV thrombolysis rate in Moldova is comparable with that in Georgia, where a low rate of the procedure is explained by lack of the rtPA treatment reimbursement.

Dysphagia screening in both Moldova and ESO-EAST countries was under-implemented compared to data from the German (86.2%) [16] or American (80% - Minnesota, 86%- Massachusetts, 88% - Ohio) registries [22].

Our study revealed severe gaps in secondary stroke prevention, especially in the use of anticoagulants for AF patients. This indicator for Romania, Lithuania and Georgia was comparable with ADSR (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Deutscher Schlaganfall-Register - German Stroke Registers Study Group) - 77.6% [16], but worse than the USA data of 93-95% [22].

The same trend was observed in the prescription of cholesterol-lowering agents. Moldova, with a 42% statin prescription rate, is significantly behind Romania, Georgia, and far from the USA registries (up to 93-96%) [22].

The RES-Q data showed a significant in-hospital stroke mortality rate in neighboring countries - Moldova and Romania, compared to the data from specialized neurological centers from Spain (3.1%) [23] and Canada (7.4%) [21]. In spite of the decrease in stroke mortality in the Republic of Moldova over the last 3 years, (from 24% in 2017 to 17% in 2018 and 15% in 2019) the rate is still quite high. The correlation between mortality rate and access to imaging services has shown unexpected results, which contradict the findings of other studies [15,23-28]. This can be explained by the country’s specific factors. Moldova is a relatively small country, which allows rapid transportation of the most severely affected patients to a better equipped centers in the capital. Therefore, regardless to the diagnostic and treatment possibilities of these hospitals, there is a high rate of stroke mortality. Furthermore, in accordance with the local traditions and culture, the severely affected stroke patients are usually referred to home long-term care provision. This trend was noticed in other studies as well [29].

The indicators related to the organization of in-hospital and post-discharge treatment did not show essential differences between Moldovan hospitals. As neurorehabilitation is rarely available, we can emphasize the fact that most of the patients are simply discharged at home. Unfortunately, this is a common situation not only for Moldova, but also for Romania and Georgia. These findings evoke the need to identify the causes of these deficiencies in order to reorganize and substantially improve the post-stroke recovery service.

Limitations

The main limitations of our study are as following: heterogeneity by number of patients included in the study by each country and between Moldovan hospitals. Ultimately, despite enlarged coverage area, not all hospitals participated and not all patients were captured. On top of that, although all the regions of Moldova are equally represented, the available data reflect the situation of only one month per year. Results from other countries may lack representativeness, but they are now the only way how to have at least some comparison with other countries with similar socioeconomic profile. Additionally, the health care systems of neighboring countries vary significantly when compared to Moldovan health care sector. Thus, because of limited accessibility, some quality indicators such as endovascular treatment, cannot serve as comparison benchmark with other countries.

Conclusion

Our study highlighted serious gaps for in-hospital stroke care performance in Moldova. The most important gaps include: the lack of CT scans in public hospitals, the absence of a national stroke centers network, extremely reduced accessibility to IV thrombolysis, and the unsatisfactory implementation of secondary stroke prevention treatment. Thus, the results of the current analysis emphasize the need to establish a National Stroke Plan supported by the government as a high priority. We need to continue the data collection in order to measure and evaluate the efficacy of implemented actions.

Competing interests

None declared

Author’s contribution

SG, NB, RM conceptualized and designed the study. EM analyzed, interpreted data, and drafted the manuscript. AG and RM contributed to the statistical analysis. All authors carried out a critical revision of the article, contributed with comments, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements and funding

The COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) Association supported the authors, project No. CA18118, IRENE COST Action -Implementation Research Network in Stroke Care Quality. Grecu A. and Mikulik R. have been supported by the project No. LQ1605 from the National Program of Sustainability II and by the IRIS-TEPUS Project No. LTC20051 from the INTER-EXCELLENCE INTER-COST program of the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic.

Authors’ ORCID IDs

Elena Manole, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0164-859X

Cristina Tiu, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8532-6218

Aleksandras Vilionskis, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0708-6946 /0000-0002-8055-3558

Alexander Tsiskaridze, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4848-4609

Eremei Zota, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1365-2633

Robert Mikulik, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7458-5166

Stanislav Groppa, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2120-2408

References

- GBD 2016 Stroke Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. Neurol., 2019; 18: 439-58.

- National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova. Available at: [https://statistica.gov.md/newsview.php?l=ro&idc=168&id=6360]. Assessed on: 10.10. 2020.

Groppa S., Efremova D., Ciobanu N. Stroke risk factors in the population of Republic of Moldova and strategies of primary prevention. Eur..Stroke.J., 2018; 3 (supl): 411.

Hoque D.M.E., Kumari V., Hoque M., et al. Impact of clinical registries on quality of patient care and clinical outcomes: A systematic review. PLoS.ONE., 2017; 12(9): e0183667.

Ringelstein E.B., Chamorro A., Kaste M., et al. ESO European Stroke Organisation Recommendations to Establish a Stroke Unit and Stroke Center Recommendations. Stroke, 2013; 44: 828-840.

Annual statistical report on the inpatient activity of medical institutions. Annex 1, form 30 (on demand). Available at: [ https://ansp.md/]. Assessed on: 19.11.2019.

The World Health Organization, The World Health Organization MONICA Project (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease): a major international collaboration. WHO MONICA Project Principal Investigators, J. Clin. Epidemiol., 1988; 41 (2): 105–114.

Registry of Stroke Care Quality. RES-Q protocol - V1.10. Available at: [https://qualityregistry.eu/images/forms/Study_Protocol_RES_Q_Formatted…]. Assessed on: 14.10.2020.

Mikulik R., Caso V., Bornstein N.M., et al. Enhancing and accelerating stroke treatment in Eastern European region: Methods and achievement of the ESO EAST program. Eur. Stroke. J., 2020; Jun, 5 (2): 204–212.

Fleet R., et al. Rural versus urban academic hospital mortality following stroke in Canada. PLoS. ONE., 2018; 13 (1): e0191151.

Gumbinger C., Reuter B., Hacke W., et al. Restriction of therapy mainly explains lower thrombolysis rates in reduced stroke service levels. Neurology, 2016; 86: 1975–83. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002695.

Seabury S., et al. Regional disparities in the quality of stroke care. Am. J. Emerg. Med., 2017; 35: 1234–1239.

- Skolarus L.E., Meurer W.J., Shanmugasundaram K., et al. Marked regional variation in acute stroke treatment among medicare beneficiaries. Stroke, 2015; Jul., 46 (7): 1890–1896.

- Aguiar de Sousa D., et al. Access to and delivery of acute ischemic stroke treatments: A survey of national scientific societies and stroke experts in 44 European countries. Eur. Stroke. J., 2019; 4 (1): 13–28.

- Berkowitz A.L. Managing acute stroke in low-resource settings. Bull. World. Health. Organ., 2016; 94 :554–556.

- Wiedmann S., Heuschmann P.U., et al. for the German Stroke Registers Study Group (ADSR). The quality of acute stroke care - an analysis of evidence-based indicators in 260 000 patients. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int., 2014; 111: 759–65.

- Lahr M.M.H., et al. Proportion of patients treated with thrombolysis in a centralized versus a decentralized acute stroke care setting. Stroke, 2012; 43: 1336-1340.

- Alvarez-Sabín J., Ribó M., Masjuan J., et al. Hospital care of stroke patients: importance of expert neurological care. Neurología (English Edition), November 2011; 26 (9): 510-517.

Powers W.J., Rabinstein A.A., et al. 2018 Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American heart association / American Stroke association. Stroke, 2018; 49 (3): e46-e99.

Navarro Soler I.M., et al. A set of care quality indicators for stroke management. Neurología, 2019; 34: 497—502.

Ganesh A., et al. The quality of treatment of hyperacute ischemic stroke in Canada: a retrospective chart audit. C.M.A.J.Open., 2014; 2 (4): 233-39.

CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention. Available at: [https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/evaluation_resources/minnesota-state-summary…]. Assessed on: 08.07.2020.

Álvarez Sabín J. In-Hospital Mortality in Stroke Patients. Rev. Esp. Cardiol., 2008; 61 (10): 1007-9.

Lekoubou A., et al. Computed tomography scanning and stroke mortality in an urban medical unit in Cameroon. E .Neurological. Sci., 2016; 2: 3–7.

Nimptsch U., Mansky T. Stroke unit care and trends of in-hospital mortality for stroke in Germany 2005-2010. Int. J. Stroke., 2014; Apr, 9 (3): 260-5. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12193.

Jørgensen H.S., Nakayama H., Raaschou H.O., et al. The effect of a stroke unit: reductions in mortality, discharge rate to nursing home, length of hospital stay and cost. A community-based study. Stroke, 1995; Jul, 26 (7): 1178-82.

Rocha M.S.G., et al. Impact of stroke unit in a public hospital on length of hospitalization and rate of early mortality of ischemic stroke patients. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr., 2013; 71 (10): 774-779.

Indredavik B., Bakke F., et al. Stroke unit care decreased mortality and increased the number of patients who were living at home 10 years after stroke. Stroke, 1999; Aug 30: 1524–7.

Nguyen T.H., Gall S., Cadilhac D.A., et al. Processes of Stroke Unite care and outcomes at discharge in Vietnam: findings of the Registry of Stroke Care Quality (RES-Q) in a major public hospital. J. Stroke. Med., 2019; 2 (2): 119-127.