Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease with an unclear etiology and complex pathogenesis. The immune response in SLE is directed against self-nuclear and non-nuclear nucleic acid-protein complexes [1]. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) is a rare autoimmune disease in which red blood cells are exposed to autoantibodies, which causes a significant decrease in their lifespan. AIHA may manifest in SLE patients at the time of diagnosis or within the first year of the disease [2]. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia manifests itself in approximately 5-10% of SLE patients [2, 3]. AIHA involves the presence of antibodies that react to heat, cold, or mixed types of reactive antibodies that are directed against antigens on the surface of red blood cells. Warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia (warm agglutinin disease) is usually manifested by asthenia and other constitutional symptoms and is diagnosed by the presence of IgG antibodies. About half of the cases of warm AIHA are recognized as secondary to the underlying disease. Warm AIHA in SLE is often associated with the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies and with an increased risk of thrombosis [4, 5].

The essential treatment of AIHA is based on suppression of autoantibody production by monotherapy or combination therapy with glucocorticoids (GC) and/or rituximab and, more rarely, with immunosuppressants such as cyclophosphamide, azathioprine. Reducing the destruction of red blood cells by splenectomy is currently considered the third-line of treatment for warm AIHA [6, 7].

Here we report a rare case of SLE with autoimmune hemolytic anemia at the onset of the disease, with relapses due to inadequate treatment in a non-compliant patient.

Case report

We report the case of a 20-year-old man, hospitalized with complaints of general weakness, asthenia, dyspnea, fever, and icteric sclera. He has a 2-year history of SLE and treatment with low dose of methylprednisolone. The onset of the disease was marked by warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Laboratory results showed a low level of hemoglobin, erythrocytes and haptoglobin and a high level of indirect bilirubin and lactate dehydrogenase, reticulocytosis.

Material and methods

Complete blood count revealed macrocytic anemia with Hb 49 g/L, RBC 0.98x1012/L, with no changes in platelet and white blood cell count. At the biochemical examination, hyperbilirubinemia with increase of both direct and indirect bilirubin (total bilirubin 71.4 μmol/L, direct bilirubin 20.71 μmol/L and indirect bilirubin 50.69 μmol/L), hypertransaminasemia (ALT 219.8 U/L, AST 178.1 U/L), decreased serum haptoglobin (0.590 g/L) and increased lactate dehydrogenase (LDH 556.4 U/L) activity were observed. The diagnose of systemic lupus erythematosus was established in accordance with the 2019 EULAR/ACR classification criteria for SLE [8-10].

Results

An 18-year-old male patient presented to the emergency unit with generalized weakness, dizziness, arthralgia, and abdominal pain. The symptoms appeared a week ago and were accompanied by a fever of 38-39°C. At the physical examination, the following were observed: pale skin, icteric sclera, local hyperemia on the fingers, ulceration in the area of the right big toe, skin peeling at the level of the fingers and toes, subacute skin rash and edema of the lower limbs. Auscultation of the lungs revealed rough vesicular breathing, dry murmurs bilaterally in basal area. The heart sounds were clear and rhythmic. Palpation of the abdomen caused pain in the epigastric region. The liver was enlarged (10 cm bellow the edge of the right rib). The spleen was enlarged to 10 cm in longitudinal diameter. Vital signs at admission: temperature 37.9°C, pulse 78 /min, BP 125/80 mmHg, RR 19 per minute and SpO2 99%. Due to severe anemia, the patient was hospitalized in the intensive care unit, where an erythrocyte mass transfusion was performed during the first 3 days (6 doses of erythrocyte concentrate).

After the improvement of the hematological indices, the patient was transferred to the rheumatology department. Physical examination showed urticaria, local hyperemia in the hands, ulceration in the area of the right big toe, peeling of the skin in the fingers and toes, signs of pruritus in the lower extremities, photosensitivity, subacute skin rash. From the patient’s medical history, it was found that the patient was diagnosed with SLE with antiphospholipid syndrome accompanied by autoimmune hemolytic anemia 3 years ago. At the onset, he presented with general asthenia, vertigo, nausea, vomiting, asthenia and fever. As the hemoglobin level was very low (72 g/l), differential diagnostic measures were taken (sternal puncture with bone marrow investigation and immunological studies). The association of hemolytic anemia with positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA on Hep2 cells, anti-dsDNA antibodies, anti-cardiolipins, anti-phospholipids, anti-Ro, Anti-Sm-B in diagnostic titer and anti-histones, Anti-Mi-2β, anti-nucleosomes, anti-RNP, Anti-Ku, anticentromere in small titer), provided strong evidence for the diagnosis of SLE according to the 2019 EULAR/ACR classification criteria of systemic lupus erythematosus. Treatment with glucocorticosteroids was initiated with a dose of 60 mg/day of Prednisone equivalent, with dose tapering in outpatient settings after stabilization of the condition. The patient did not comply with the medical prescriptions, and rapidly reduced the dose of Methylprednisolone eventually discontinuing it completely. Upon discontinuation of treatment, symptoms of clinical exacerbation and signs of hemolytic anemia reappeared.

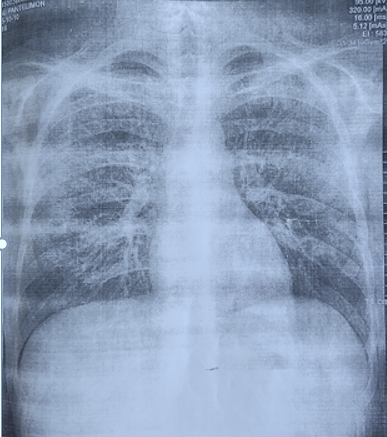

During the last hospitalization, measures were taken to rule out digestive hemorrhage and assess the extent of internal organ damage. Fibrogastroduodenoscopy revealed catarrhal gastritis without signs of hemorrhage, and the abdominal ultrasound examination revealed hepatomegaly and splenomegaly. No obvious changes on transthoracic echocardiography. X-ray examination of the chest demonstrates interstitial lung involvement (Fig. 1).

Laboratory results are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Hematological parameters of patient during hospitalization | ||||||||

Parameter | Date | Reference range | Units | |||||

15.03 | 16.03 | 17.03 | 18.03 | 19.03 | 22.03 | |||

Hemoglobin | 49 | 61 | 76 | 92 | 102 | 100 | 130-170 | g/L |

Hematocrit | 13.4 | 17 | 21 | 25 | 28.7 | 28.6 | 39-54 | % |

Red blood cells | 0.89 | 1.31 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.49 | 2.54 | 4.0-6.0 | *10^12/L |

Platelets | 205 | 155 | 118 | 126 | 160 | 238 | 150-450 | *10^9/L |

MCV | 150.6 | 132.3 | 123.7 | 118.3 | 115.3 | 112.6 | 78-95 | fL |

MCH | 55.1 | 46.9 | 45.0 | 43.2 | 41.0 | 39.4 | 27-36 | pg |

MCHC | 36.6 | 35.5 | 36.4 | 36.5 | 35.5 | 35.0 | 32-36 | g/dL |

PDW | 9.5 | 9.3 | 9.3 | 11.0 | 10.4 | 9.6 | 11-16.6 | fL |

MPV | 10.0 | 9.9 | 9.7 | 10.1 | 10.0 | 9.5 | 7.4-11.0 | fL |

P-LCR | 23.6 | 23.3 | 22.3 | 25.7 | 24.1 | 20.8 | 13-43 | % |

White blood cells | 12.45 | 6.7 | 3.9 | 3.5 | 3.92 | 4.83 | 3.6-10.0 | *10^9/L |

Neutrophils | 82.9 | 72 | 56 | 55 | 66.7 | 65.2 | 42.2-75.2 | % |

Eosinophils | 0.2 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 3 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 0-4.0 | % |

Basophiles | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0-0.6 | % |

Monocytes | 6.3 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 7.7 | 11.6 | 2.2-8.0 | % |

Lymphocytes | 10.4 1.29 | 19 1.29 | 31 1.22 | 31 1.07 | 21.7 0.85 | 23.2 1.12 | 20.5-45.0 1-4 | % *10^9/L) |

ESR |

| 27 | 26 | 24 | 6 | 5 |

| mm/h |

Reticulocytes |

|

|

|

| 170.9 |

| 0.2-1.0 | % |

Morphology | Macrocytosis |

|

|

| Macrocytosis | Macrocytosis |

|

|

Note: MCV - mean corpuscular volume; MCH - mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC - mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; PDW - platelet distribution width; MPV - mean platelet volume; P-LCR - platelet-large cell ratio; ESR - erythrocyte sedimentation rate. | ||||||||

Table 2. Biochemical parameters of patient during hospitalization | |||||||

Parameter | Date | Reference range | Units | ||||

15/03 | 16/03 | 17/03 | 18/03 | 22/03 | |||

Total bilirubin | 71.4 | 54.4 | 39.2 | 33.9 | 14.57 | 2.0-21.0 | μmol/L |

Direct bilirubin | 20.71 | 16.4 | 13.7 | 11.4 |

| <5.13 | |

Indirect bilirubin | 50.69 | 38.0 | 25.5 | 22.5 |

| <16.4 | µmol/L |

AST | 123 | 68 | 37 | 12.7 | <35 | U/L | |

ALT | 160 | 109 | 74 | 22.9 | <45 | U/L | |

Urea | 9.27 | 8.3 | 6.5 | 5.7 | 7.70 | 2.8-7.2 | mmol/L |

Creatinine | 134.3 | 106 | 72 | 58 | 47.9 | 70-115 | μmol/L |

Amylase | 63.7 |

|

|

|

| 28-100 | U/L |

Albumin |

|

|

|

| 28.6 | 35-53 | g/l |

y-GT |

|

|

|

| 34.0 | 11-50 | U/L |

LDH |

|

|

|

| 240-480 | U/L | |

CRP |

|

|

|

| 2.7 | <5 | mg/L |

RF |

|

|

|

| 6.0 | 0-15 | IU/mL |

Na |

|

|

|

| 142.0 | 130-157 | mmol/l |

K |

|

|

|

| 4.18 | 3.6-5.- | mmol/l |

Haptoglobin |

|

|

|

| 0.9-2.2 | g/L | |

Note: AST – aspartate aminotransferase; ALT- alanine aminotransferase; y-GT - gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; LDH - lactate dehydrogenase; CRP – C-reactive protein; RF – rheumatoid factor; Na - sodium; K - potassium. | |||||||

The physical examination revealed clinical signs characteristic of the evolution of systemic lupus erythematosus, such as acute photosensitive skin rash, necrotizing vasculitis in the fingers, scratching lesions and livedo reticularis (Fig. 2)

|

Fig 1. Chest X-ray with diffuse interstitial lung involvement most characteristic for lupus pneumonitis |

|

|

|

|

Fig 2. Skin manifestations observed in the patient A, B - subacute skin rash, C - necrotizing digital vasculitis, D - scratching lesions | |

In the rheumatology department, high doses of glucocorticoids (Methylprednisolone 250 mg intravenously for 3 days as pulse therapy) were initiated, followed by prolonged treatment with Prednisolone 40 mg/day per os with dose adjustment depending on the effectiveness of the treatment measured by validated tools.

On the third day after the installation of the peripheral venous catheter (ulnar vein) pain, swelling and hyperemia in the area of the venipuncture appeared. The catheter was removed, and the vascular Doppler examination detected a non-occlusive thrombosis of the veins of the upper arm. Administration of Clexane at a dose of 2000 Un/day resolved this process.

As can be seen in the case presented by us, not all the elements of AIHA are manifest. Its peculiarities include anemia with macro- and anisocytosis, hyperbilirubinemia, hypohaptglobinemia and increased liver enzymes (AST, ALT, LDH), with an absence of thrombocytopenia. The presence of AIHA is associated with a more severe course of the disease, onset at a young age and multisystemic involvement (pulmonary, joint, vascular, thrombotic events). Non-compliance worsens the symptoms, futher endangering the patient's life.

Discussion

SLE is a systemic autoimmune disease in which tolerance to one's own antigens is lost. Autoantibodies cause cell and tissue destruction through cytotoxicity reactions or the formation of immune complexes. It can affect any organ, the initial symptoms are often non-specific, and the correct diagnosis is difficult. Women of childbearing age are more frequently affected, only approximately 10% of patients are men [1].

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia may be the first manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus and can occur several years before the diagnosis of SLE is established. For differential diagnosis, the authors recommend the determination of SLE (specific antinuclear antibody) marker tests in the presence of symptoms characteristic of the disease, using the 2019 EULAR/ACR diagnostic criteria. Among these criteria is autoimmune hemolytic anemia (which contributes 4 points in favor of the diagnosis of SLE) [8-10]. Hemolytic anemia in patients with SLE is rare and is possibly caused by anti-erythrocyte or microangiopathic antibodies [2-5].

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in patients with SLE can be the cause of various complications and multi-organ damage. The risk of ischemia and thrombotic events should not be overlooked, as the products of hemolysis are toxic to several cell types and tissues. Excess iron and hemoglobin can also affect the kidneys, especially in those with lupus nephritis.

González LA et al. in a Latin American cohort study (2023) on a group of 1364 patients with lupus, mentions that severe AIHA is observed in about 3.6% of patients, particularly at the onset of the disease. Male sex and high activity of the disease are risk factors for its development. The authors hypothesize that hematological manifestations in a patient with SLE could predict the occurrence of AIHA in the near future [11].

Turk E. et al. (2024) in a large Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), conclude that AIHA contributes to the increased mortality of patients with SLE due to acute myocardial infarction, cerebral stroke.They emphasize that AIHA must be promptly diagnosed in patients with lupus, considering it an unfavorable risk factor related to patient mortality [6].

At present, there is no broad consensus on the treatment of SLE patients. It depends on the clinical manifestations and activity of the disease, damage to life-threatening organs (lungs, heart, kidneys, nervous system). Most authors consider the use of corticosteroids in patients with AIHA to be appropriate, with a gradual reduction of the dose once a stable clinical effect is achieved, in order to reach an adequate maintenance dose. The role of immunosuppressors in the treatment of AIHA is not well defined. Some authors show the efficacy of Rituximab in the treatment of patients with SLE and AIHA [7].

Conclusions

The particularities of this clinical case confirm the severity of the evolution of systemic lupus erythematosus in association with autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Intensive treatment with corticosteroids along with erythrocyte mass transfusions for the correction of anemia at the onset of this syndrome, as well as in cases of relapse, is effective in most instances. Once the desired effect is achieved, the dose of CS should be gradually reduced until an effective maintenance dose is reached. In refractory cases, it is necessary to consider the administration of immunosuppressors, such as Rituximab. Further research is needed to evaluate predictive factors, as well as to discover new drugs effective in patient management.

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors’ contribution

SP, SA devised the main conceptual ideas of the paper. VT, LD drafted the manuscript. LD, VT, VC collected the data from patient. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Informed consent for publication

Obtained.

Funding

None.

Authors’ ORCID IDs

Vera Tcaci – https://orcid.org/0009-0007-6435-7673

Serghei Popa – https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9348-4187

Svetlana Agachi – https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2569-7188

Lucia Dutca – https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1815-2294

Valeriu Corotaș – https://orcid.org/0009-0008-2552-4720

References

Systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Groppa L, Popa S, Rotaru L, et al. Rheumatology and nephrology: Textbook. Chișinău: Lexon Prim; 2019. p. 98-120. ISBN 978-9975-3344-1-9.

Domiciano DS, Shinjo SK. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in systemic lupus erythematosus: association with thrombocytopenia. Clin Rheumatol. 2010 Dec;29(12):1427-31. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1479-2.

Lu Y, Huang XM. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia as an initial presentation in children with systemic lupus erythematosus: two case reports. J Int Med Res. 2022 Aug;50(8):3000605221115390. doi: 10.1177/03000605221115390.

Kokori SI, Ioannidis JP, Voulgarelis M, Tzioufas AG, Moutsopoulos HM. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Med. 2000;108(3):198-204. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00413-1.

Gormezano NWS, Kern D, Pereira OL, et al. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in systemic lupus erythematosus at diagnosis: differences between pediatric and adult patients. Lupus. 2017;26(4):426-430. doi: 10.1177/0961203316676379.

Turk E, Deenadayalan V, Obeidat K, Rodriguez P. Outcomes of autoimmune hemolytic anemia in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a nationwide inpatient sample study [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022;74(Suppl 9) [cited 2024 Apr 12]. Available from: https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/outcomes-of-autoimmune-hemolytic-anem…

Pavo-Blanco M, Novella-Navarro M, Cáliz-Cáliz R, Ferrer-González MA. Rituximab in refractory autoimmune hemolytic anemia in systemic lupus erythematosus. Reumatol Clin. 2018;14(4):248-249. doi: 10.1016/j.reumae.2017.07.007.

Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, Brinks R, Mosca M, Ramsey-Goldman R, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Sep;71(9):1400-1412. doi: 10.1002/art.40930.

Ameer M, Chaudhry H, Mushtaq J, et al. An overview of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) pathogenesis, classification, and management. Cureus. 2022;14(10):e30330. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30330.

Fanouriakis A, Tziolos N, Bertsias G, et al. Update in the diagnosis and management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:14-25. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218272.

González LA, Alarcón GS, Harvey GB, et al. Predictors of severe hemolytic anemia and its impact on major outcomes in systemic lupus erythematosus: data from a multiethnic Latin American cohort. Lupus. 2023;32(5):658-667. doi: 10.1177/09612033231163745.

A

A B

B C

C D

D