Introduction

Acute appendicitis (AA) is among the three most commonly occurring acute surgical diseases. The likelihood of experiencing AA in a lifetime is approximately 7%. The incidence of AA reduces with age after adolescence [1]. Approximately 15% of patients over 60 years of age who present with acute abdominal pain to the Emergency Department receive a final diagnosis of acute appendicitis, which is half as common as in younger patients [2]. Nevertheless, the epidemiology and outcomes of acute appendicitis in elderly patients differ significantly from those of the younger population. First, despite the decrease in incidence, acute appendicitis in elderly patients is marked by significantly higher mortality, which is 8% in the category of patients over 60 years of age, compared to less than 1% among younger patients. A large observational study of 164,579 patients with acute appendicitis, age greater than 60 years was a significant risk factor for mortality by multivariate analysis [3].

All the data suggest that older patients are more likely to have complicated appendicitis with perforation or abscessing compared with other age groups. The rate of complicated appendicitis ranges from 18% to 70% [2, 4-6] (compared to a rate of 3 % and 29% among patients under 60 years). The reason for this major risk of perforation could be the vascular sclerosis that the vermiform appendix develops in elderly patients and the narrowing of the lumen by the phenomenon of fibrosis. In these patients, the muscle layers are infiltrated with fat, so having a fragile structure they have a tendency toward early perforation [7]. These findings together with the delay in diagnosis and treatment could explain a more aggressive evolution of the disease in this population category.

Another finding among the elderly population, who develop acute appendicitis, is the lower rate of correct preoperative diagnosis compared to the younger population [8], with a reported diagnostic accuracy (defined as the percentage of appendices removed with a histological diagnosis of acute appendicitis out of the total number of appendectomies performed) of 64% in patients over 60 years of age versus 78% in other age groups [9]. Moreover, in the vast majority of included studies, the mean time from symptom onset to admission was longer in older patients than in younger patients [9-11].

Focusing on appendectomy, compared with young patients, elderly patients are burdened with higher postoperative mortality, higher postoperative morbidity [12], longer length of hospital stay [13], lower rate of laparoscopic appendectomy, and a higher risk of being subjected to high-throughput investigations [14-15].

In a large Swedish study that included more than 117,000 patients, the mortality rate after appendectomy was strongly influenced by age, with a threefold increase for each decade of age, reaching more than 16% in nonagenarians. Finally, the complication rate in elderly patients with negative appendectomy was significantly higher than in younger patients (25% vs 3%) [16].

This raises the question of whether existing clinical scoring systems have sufficient diagnostic accuracy for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in elderly patients?

According to the Jerusalem guidelines [18], in adult patients the Alvarado score (with a cut-off score < 5) is sensitive enough to exclude acute appendicitis, but is not specific enough in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis.

However, the Alvarado score was developed based on the pattern of presentation of clinical and laboratory variables of a young population (mean age 23.4 - 25.9) [19]. Considering that the complication rate in elderly patients with negative appendectomy is significantly higher than in younger patients (25% vs 3%, p < 0.05) [20], the preoperative diagnosis in these patients must be as accurate as possible.

Although computer tomography (CT) with intravenous (IV) contrast is associated with lower rates of negative appendectomy [21]. Ultrasound (US) is clearly inferior to CT in sensitivity and negative predictive value for appendicitis, however, it may be equally useful for excluding appendicitis [22, 23], while CT is especially useful if the appendix is not visualized by US.

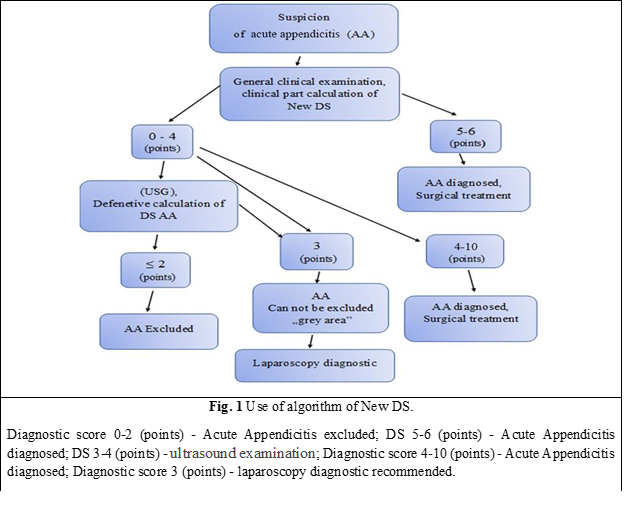

The New diagnostic score (DS), which we aimed to compare with the Alvarado score, is a diagnostic score that includes 10 parameters: the positive Kocher symptom- 1 point; positive Blumberg symptom in the right iliac region - 2 points; positive Bartomier-Michelson symptom - 1 point; the presence of nausea and/or vomiting - 1 point; leukocytosis in Complete Blood Count (CBC) 10 x 109/l and more - 1 point; ultrasound determination of Vermiform Appendix (VA) with a diameter greater than 7 mm is estimated at 2 points; VA incompressibility - 1 point; thickening of the peri-appendiceal tissue - 1 point; coprolite in the VA lumen - 1 point; the presence of ultrasound signs of another acute non-appendiceal pathology of the abdominal cavity and/or ultrasound detection of a compressible VA less than 7 mm in diameter - „minus” 3 points.

In this scoring system, the total score varies between -3 and 10 points. When obtaining a score below 2 points, the diagnosis of AA is excluded. If adding up the points of the positive clinical and laboratory criteria of AA, a result of 6-7 points will be obtained, and then the diagnosis of AA will be established. In this case, an additional ultrasound will not be necessary, because even the identification of another acute pathology with / or without signs of inflammation of vermiform appendix on UST („minus” 3 points), will not affect the result and the interpretation of the New DS application algorithm, because the final score will be 3 or more points, which definitely indicates that the patient has AA. The patient diagnosed with AA will later undergo urgent surgical treatment.

If the sum of the points of the clinical and laboratory criteria of the New DS will be less than 4 points, an ultrasound of the abdominal cavity will be performed with the additional inclusion of ultrasound signs of AA. If following a general ultrasound examination, the sum of AA points will constitute < 2 points, the diagnosis of AA will be excluded.

When following the general ultrasound evaluation of signs of AA, the number of points will be 3 or more, the diagnosis of AA will be very likely and appendectomy will be indicated.

Material and methods

There were prospectively analyzed 78 cases (patients), who were admitted to the Emergency Department of Saint Archangel Michael Municipal Clinical Hospital in 2018-2022 with the diagnosis of acute appendicitis (AA). Of all hospitalized patients, AA was confirmed on histological examination in 22 (28.2%) patients.

The average age of patients was 73.5±13.5 years (minimum - 60 years, maximum - 87 years). The ratio of males to females was 1:1.6. Demographic data of patients, including age, sex, duration of hospitalization, and histopathological reports of appendectomy materials were recorded. Analyzing the obtained data, we note that the structure of distribution by sex and age in this group of patients is comparable to that in the group of patients in which the new DS was developed.

The time from the debut of complaints of abdominal pain to hospitalization was: in 9 (11.5%) people - less than 6 hours, from 6 hours to 24 hours - in 28 (35.9%) patients, from 24 hours to 48 hours - in 22 (28.3%) patients, more than 48 hours - in 19 (24.3%) patients.

After data processing, the patients admitted to the study group had the concomitant pathologies noted in table 1.

Table 1. Patient demographic data and characteristics | ||||

| Associated medical conditions | № | % | |

1. | Hypertension | 37 | 47.4 | |

2. | Coronary heart disease | 20 | 25.6 | |

3. | Diabetes | 11 | 14.1 | |

4. | Obesity | 5 | 6.4 | |

5. | Dyscirculatory encephalopathy | 14 | 17.9 | |

6. | Urolithiasis | 7 | 8.9 | |

7. | Chronic duodenal ulcer | 4 | 5.1 | |

8. | Chronic gynecological pathologies without exacerbation | Uterine myoma | 3 | 3.8 |

Uterovaginal prolapse | 2 | 2.6 | ||

Pelvic inflammatory disease | 2 | 2.6 | ||

Statistical analysis

The SPSS 18 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Numerical data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. The one-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the distribution of numerical data. The independent sample t-test was used when the distribution was normal and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for the non-normal distribution. A chi-square test was used to compare between groups. Values with a P value < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

New DS in AA implementation results

In this group of patients, the non-standardized clinical and ultrasonographic diagnosis of AA was used as the main diagnostic method, which was performed by the doctor on call, based on professional knowledge and skills, in the absence of a mandatory research standard and an algorithm for interpreting the obtained data, which is largely subjective. In the Emergency department, the non-standardized diagnosis of AA was made based on clinical, laboratory, and ultrasonographic investigations. The method of diagnosis and the clinical-therapeutic tactic used for all groups of patients were methodologically similar to this diagnostic method (New DS) (Table 2), and its algorithm, which corresponds to all the training principles of the diagnostic algorithm (Fig. 1).

Table 2. The New Diagnostic Score. | |||

No. | Criterion | Assessment | Score |

1. | Kocher symptom | Positive | 1 |

2. | Nausea /vomiting | Present | 1 |

3. | Blumberg symptom in right iliac region | Positive | 1 |

4. | Bartomier-Michelson symptom | Positive | 1 |

5. | Leukocytosis | >10 × 109/l | 1 |

6. | Ultrasound: VA unchanged and /or other pathology | Determined | -3 |

7. | Ultrasound: increased VA diameter > 7mm | Determined | 2 |

8. | Ultrasound: thickening periappendicular tissue | Determined | 1 |

9. | Ultrasound: VA Incompressibility | Determined | 1 |

10. | Ultrasound: coprolite in VA lumen | Determined | 1 |

| Total | Max Min | 10 -3 |

Note: VA - vermiform appendix; the total score is a sum of criteria points. Minimal Score (-3), maximum (10). | |||

All patients were examined using the same diagnostic equipment. The non-standardized clinical and ultrasonographic method included the use of a general clinical examination, laboratory investigations (CBC, urinalysis), ultrasonography (USG) of the abdominal cavity.

The diagnosis and management of AA patients were specified directly by the on-call surgeon. The general clinical examination was performed in all 78 (100%) patients and consisted of collecting anamnesis, and patient complaints to determine the symptoms of AA with their subsequent interpretation.

Patients in the study group presented the following complaints (Table 3).

Table 3. Diagnostic criteria of patients | |||

No. | Diagnostic criteria | Patients | |

No. | % | ||

1 | Abdominal pain | 78 | 100 |

2 | Nausea | 30 | 38.5 |

3 | Vomiting | 41 | 52.5 |

4 | Kocher's symptoms | 32 | 41.0 |

5 | Gynecological anamnesis | 7 | 9 |

6 | Intestinal disorders (constipation) | 64 | 82.9 |

7 | Dysuria | 37 | 47.4 |

8 | Local tenderness (pain) (on palpation in the right iliac region) | 78 | 100 |

9 | Blumberg's symptom in the right iliac region | 78 | 100 |

10 | Bartomier-Michelson's symptom | 56 | 71.8 |

11 | Rovzing's symptom | 44 | 56.4 |

12 | Sitkovsky's symptom | 54 | 69.2 |

13 | Obraztsov's symptom | 3 | 3.8 |

14 | Coupe's symptom | 2 | 2.5 |

15 | Voscresenscky symptom | 2 | 2.5 |

16 | Hyperthermia >37.4oC | 65 | 83.3 |

17 | Tenderness on palpation of the anterior rectal wall | 3 | 3.8 |

18 | Leukocytosis >10×109/l | 78 | 100 |

19 | Deviation of the leukocyte formula >74% | 78 | 100 |

20 | Hematuria, leukocyturia | 78 | 100 |

21 | Free fluid in the abdominal cavity | 78 | 100 |

22 | US signs of unchanged VA or other pathologies of the right iliac region | 43 | 55.1 |

Note: US – ultrasound; VA - vermiform appendix. | |||

Results of laboratory examinations of patients

In examined patients, the increase in the number of leukocytes in complete blood count (CBC) >10x109/l was detected in 70 (89.7%) patients. Left shift of (increased neutrophil ratio) more than 74% was found in 58 (74.3%) patients.

Left shift of (increased granulocytes ratio) more than > 6% was found in 47 (60.25%) examined patients. The absence of pathological changes (leukocyturia, hematuria, bacteriuria) in the urinalysis was observed in 44 (56.4%) of the examined patients. Leukocyturia/hematuria was found in 34 (43.5%) cases.

Results of ultrasound

The following ultrasonographic signs were recorded in the examined patients:

AV diameter increase > 7 mm was determined in 30 (38.4%) patients.

AV incompressibility during compression was observed in 28 (35.8%) patients.

Positive „Target” symptom was detected in 39 (50%) of the examined patients.

Coprolite in the VA lumen was detected in 5 (6.4%) patients.

Thickening of the peri-appendiceal tissue was detected in 16 (20.5%) of the examined patients.

Free liquid in the abdominal cavity was detected in 28 (35.8%) patients.

Increased blood flow in the VA wall during Doppler examination was observed in 17 (21.7%) patients.

In 23 (29.4%) of the examined patients, ultrasound signs of unchanged AV or other pathologies of the right lower quadrant of the abdomen were detected. The distinctive feature of establishing the diagnosis through a DS is that the surgeon has the possibility of interpreting the results of investigations and symptoms in three categories: positive, negative, and doubtful, which, in our opinion, largely depends on personal qualification and experience. Laboratory diagnosis consisted of CBC and urinalysis, which were performed in all patients included in the clinical trial. In 13 (16.6%) patients, additional biochemical blood analysis was performed (amylase level, urea, creatinine, serum protein level, and bilirubin). Blood glucose analysis was performed in 56 (71.7 %) patients.

Examination of the ultrasound signs of AA can confirm or deny the diagnosis, as well as exclude abdominal surgical pathologies of the gallbladder and pancreas, and some gynecological pathologies.

Overall radiography of the abdomen was performed in 19 (24.3%) patients. Additionally, a gynecologist consulted 12 (15.3%) patients.

Following the examination, the patients were divided into three groups: the first group of patients, who underwent emergency surgery for AA; the second group of patients - who „accumulated” insufficient data to exclude or to confirm AA, and in our proposed algorithm for the implementation of the New DS was designated by us as a „grey area”, and the third group of patients - in which the diagnosis of AA was excluded.

In the group of patients, in which AA was excluded, ulcer disease was diagnosed, chronic duodenal ulcer in exacerbation - 2 cases, urolithiasis, right renal colic - 1 case, acute pancreatitis - 2 cases, pelvic inflammatory disease - 2 cases, myxomatous node necrosis - 1, cr. Right ovarian cancer - 1 case, cancer. of cecum - 1, and functional bowel disorders - 3 (3.8%) cases.

Patients who did not „accumulate” enough data to exclude and confirm AA, 3 (3.8%) were admitted to the hospital, where they were evaluated and monitored dynamically for 72 hours. In all these patients, the diagnosis of AA was excluded.

Diagnostic laparoscopy was performed in 11 (14.1%) patients, of which 6 (5.1%) patients subsequently underwent laparoscopic appendectomy. From this group (laparoscopy + laparotomy) in 5 (6.4%) patients the diagnosis of AA was confirmed histologically. „Negative” appendectomy due to intraoperative overdiagnosis of AA was performed in one case. Based on the results of diagnostic laparoscopy, AA was excluded in 5 (6.4%) patients. The pathologies diagnosed by diagnostic laparoscopy were destructive acute appendicitis (AA) in 5 (6.4%) patients, simple acute appendicitis in 1 (1.2%) case, terminal ileitis in 1 patient, necrosis of the mammary nodule in 1 patient, ovarian cancer on the right in 2 patients, functional disorders of the intestine in 1 patient.

Patients in whom the diagnosis of AA was established based on the results obtained from the non-standardized diagnosis, underwent emergency surgical treatment, and laparoscopic appendectomy. At the histopathological examination, the diagnosis of AA was confirmed in 39 (73.5%) of the number of patients initially operated on – 53 (100%) cases. 14 (26.8%) people were found to have undergone „negative” appendectomy. Of 59 (75.6%) patients who underwent appendectomy (initial or after diagnostic laparoscopy), the diagnosis was confirmed in 44 (74.5%) and non-destructive forms of AA were established in 15 (26.4%) patients.

Following the analysis of the „negative” appendectomy protocols, it was demonstrated that in 8 (53.3%) cases, the non-destructive form of VA inflammation was diagnosed by the surgeon intraoperatively, but the appendectomy was still performed due to the surgical approach in the already present right iliac region. In 7 (46.7%) cases, an intraoperative hyper-diagnosis of AA was found, but it was not histologically confirmed.

Overall, AA was histologically confirmed in 45 (57.6%) patients, and in 33 (42.4%) patients, this diagnosis was excluded. Typical VA localization was observed in 31 patients (68.8% of the total number of operated patients). The atypical location of the VA was observed in 14 (31.2%) patients.

New DS implementation results

In parallel with the non-standardized clinical-paraclinical diagnosis of AA, in the group of patients under study, an assessment based on certain criteria of AA symptoms was performed based on the New DS. According to the New DS, the following diagnostic criteria were recorded in the study group: positive Kocher symptom in 9 (11.5%) patients; nausea and/or vomiting in 41 (52.5%) patients; the positive Shchetkin-Blumberg symptom in the right iliac region in 25 (32%) patients; positive Bartomier-Michelson symptom in 17 (21.7%) patients; leukocytosis >10 x 109/l - in 39 (50%) patients.

The ultrasound data obtained in the patients of this study group showed that the determination of signs of another pathology and/or VA without signs of inflammation was detected in 20 (25.6%) patients; volume increase of VA diameter greater than 7 mm in 21 (26.9%) patients; AV incompressibility was determined in 19 (24.3%) patients; coprolite in the VA lumen - in 4 (5.1%) patients; thickening of the peri-appendiceal tissue - in 16 (20.5%) patients.

Considering that the indications for surgical treatment were established based on New DS, appendectomy was performed in 30 (38.2%) patients from the study group. With the sum of New DS scores >3, surgical intervention was performed in 27 (90%) cases, and histologically AA was confirmed in 21 (70%) patients. In 7 (8.9%) cases from this group of patients, based on the New DS, the diagnosis of AA was excluded, respectively, surgical treatment was avoided. Subsequently, those patients no longer requested specialized medical help.

Patients who accumulated 2 points – 6 (7.6%) cases, were assigned to the „grey area” of the New DS, of which 3 patients underwent diagnostic laparoscopy and subsequent appendectomy through laparotomy in one case. AA was histologically confirmed in 1 patient. The others – 4 (57.2%) patients, avoided appendectomy, AA being excluded. None of the patients with excluded AA required further medical attention.

Out of 41 (52.7%) patients with total New DS results < 2, surgery was performed in 31 (75.6%) patients. Histological AA was confirmed in 5 (12%) patients. The other 10 (24.4%) patients were not operated on, AA being excluded.

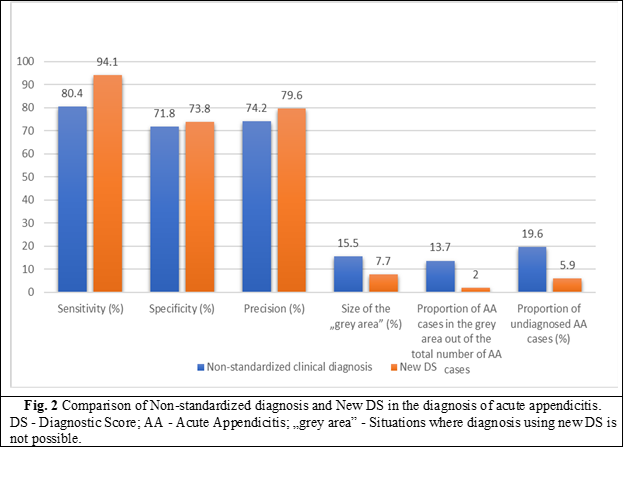

When evaluating the effectiveness of the New Diagnostic Score, the following results were obtained: sensitivity - 94.1%, specificity - 73.8%, precision - 79.6%, the size of the „grey area” - 7.6%, the proportion of AA in the „grey area” of the total amount of AA - 4.3%, the proportion of undiagnosed AA cases - 5.9%.

Comparative evaluation of the effectiveness indicators of the New DS. The comparative analysis of the New DS and the non-standardized diagnosis demonstrated the superiority of the respective indicators and the effectiveness of the diagnostic score. The high sensitivity of the New Diagnostic Score was statistically demonstrated (ƛ2 = 4.32; p < 0.05), a lower rate of missed AA cases in New Diagnostic Score (ƛ2 = 4.32; p < 0.05), the „grey area” is smaller in New SD (ƛ2 = 5.28; p < 0.05) than by non-standardized diagnosis. A lower rate of AA cases in the „grey area” of the total AA cases was demonstrated (ƛ2 = 4.9; p < 0.05).

Based on these data, the comparative evaluation indicators such as specificity and diagnostic accuracy did not show significant statistical differences. At the same time, a definite increase in specificity and accuracy is noted in the case of New DS compared to the non-standardized clinical diagnosis.

Risk factors in the diagnosis of AA and evaluation of their impact on the effectiveness of the New DS

In specialized literature, it is indicated that it is difficult to diagnose AA using the clinical method and unstandardized DS in female patients, at a young age, in patients with atypical VA localization, obesity, and in geriatric patients. This leads to false positive and false negative diagnoses of AA [24 - 27]. We consider these circumstances as risk factors for the clinical diagnosis of AA. Considering the fact that New DS is based on clinical data, we conclude that this criterion may affect its performance indicators.

We considered necessary to study the effectiveness of the New DS in the presence of the indicated risk factors. We evaluated the performance indicators of New DS in the subpopulation with risk factors - obesity, atypical location of VA.

Table 4. Effectiveness of the New DS analysis according to risk factors | ||||||

No. | Indicator of performance | General | Atypical location of VA

| р* | Obesity BMI >25 kg/m2 | р* |

1 | Sensitivity (%) | 93.15 | 92.2 | >0.05 | 93.8 | >0.05 |

2 | Specificity (%) | 73.06 | 72.3 | >0.05 | 68.3 | >0.05 |

3 | Precision (%) | 78.8 | 77.8 | >0.05 | 79.5 | >0.05 |

4 | The size of „the grey area” (%) | 7.5 | 8.3 | >0.05 | 5.5 | >0.05 |

5 | The proportion of ADA from the „grey area” out of the total number of AA (%) | 2 | 0 | >0.05 | 3.1 | >0.05 |

6 | The ratio of undiagnosed cases of AA (%) | 5.84 | 0 | >0.05 | 3.1 | >0.05 |

Note: VA - vermiform appendix; BMI - body mass index; p - coefficient; ADA -acute destructive appendicitis; AA - acute appendicitis; „grey area” - Situations where diagnosis using new DS is not possible. | ||||||

Thus, the use of the New Diagnostic Score for the selected subpopulations did not demonstrate statistically significant differences in performance indicators compared to the universal population. This fact indicates the possibility of the universal application of the New DS developed by us on the population of elderly and senile patients, excluding people with central nervous system injuries, as well as obese patients. The sensitivity of New DS in typical localization of VA was 94.1% and in the atypical one - 92.2%. Thus, the atypical location of the AV does not affect the sensitivity of the New DS.

Comparative evaluation of the clinical efficacy of New DS and DS Alvarado.

According to the Jerusalem guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute appendicitis in the general population, which recommend the use of scoring systems for the exclusion of AA in elderly patients compared to the low-probability score - DS AA Alvarado, we performed an analysis of the effectiveness of the New DS.

Few studies have evaluated the applicability of existing appendicitis diagnostic scores in the elderly population [28, 29]. A retrospective study of 96 patients over 65 years of age demonstrated that the use of the Alvarado scoring system, with a cut-off of 5, maintains reliability in elderly patients. In fact, the vast majority of patients with morpho-pathologically confirmed appendicitis (86.6%) had an Alvarado score ranging from 5 to 8 and 40% a score of 5 or 6. According to these data, Alvarado scores ranging from 5 to 10 should correspond to an increased risk of appendicitis in the elderly. Another retrospective study performed on 41 patients aged over 65 years presented an area under the curve (AUC) of the Alvarado score for this population of 96.9% with 100% negative and positive predictive values of the two cut-off points of 3 and 6 [30]. In the absence of high-quality evidence dedicated to the elderly, the multitude of experts could not make a strong recommendation; The Alvarado score is suggested for excluding but not diagnosing appendicitis in elderly patients, with a conditional recommendation based on low-quality evidence.

Another Diagnostic Score of acute appendicitis Tzanakis did not include the analysis performed, since, according to the structural-comparative analysis of it and its application algorithm, a very important diagnostic concept is missing in its structure, namely the presence of the „grey area”, due to which, according to the data of the specialized literature, an unacceptably high number of non-destructive forms of AA was admitted (54% of operated patients), which is currently a very low indicator of the clinical efficiency of AA diagnosis.

Also, a comparative evaluation of the clinical effectiveness of the original clinical score with the RIPASA, Christian, Lintula scores, which are not focused on the diagnosis of destructive forms of AA, being developed on the basis of retrospective studies, without using statistical methods to calculate the diagnostic efficiency (MStA), was not performed.

In accordance with the recommendations of the National Clinical Protocol for the diagnosis and treatment of acute Appendicitis adopted and approved by the Moldovan Nicolae Anestiadi Association of Surgeons, all examined patients, according to DS AA Alvarado, were assigned as follows:

0-4 points (AA is unlikely) – 31 (39.7%) patients;

5-6 points (AA is possible and the patient needs observation) – 20 (25.6%) patients;

7-8 points (AA is probable) – 22 (28.2%) patients;

9-10 points (AA confirmed and the patient needs urgent surgical treatment) – 5 (6.4%) patients.

At the same time, we recommend that patients with score results of 7-8 and 9-10 points to be combined into one group, because the formulation of the algorithm for patients of these groups is ambiguous, AA being diagnosed in both cases, constituting 27 (34.6%) patients.

In 27 (34.7%) patients with a score between 7-10 points, surgery was performed in 18 (66.7%) cases. In 9 (33.3%) patients the diagnosis of AA was excluded without surgical intervention. Histologically AA was confirmed in 12 (44.4%) patients.

In 20 (25.6%) patients, with a score of 5-6, 17 (85%) patients underwent surgery, of which in 3 (15%) patients, the diagnosis of AA was excluded without surgery. Histologically AA was confirmed in 6 (30.0%) patients.

In 31 (39.7%) patients, with a score of 0-4, 26 (83.8%) patients underwent surgery; in 5 (16.2%) patients, the diagnosis of AA was excluded without surgery. Histologically AA was confirmed in 9 (29.0%) patients.

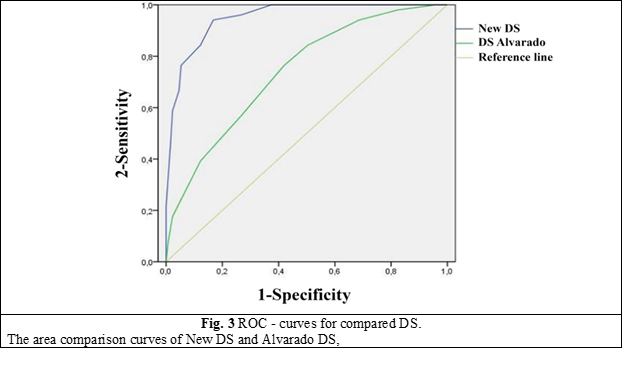

For a comparative evaluation of New DS with DS Alvarado with the help of the PASW Statistics 18 program, ROC analysis was performed with the construction of the corresponding curves (Fig. 3).

The area under the curve for New DS was found to be statistically significantly higher compared to DS Alvarado and amounted to 0.95, which corresponds to the excellent quality indicator of the statistical model.

Table 5. ROC metrics (area under the curve) of New DS and Alvarado DS | |||

Diagnostic scores | The area under the curve | 95% - confidence interval | |

New DS | 0.952 | 0.924 | 0.981 |

Alvarado DS | 0.739 | 0.662 | 0.816 |

Note:The area comparison curves of New DS and Alvarado DS | |||

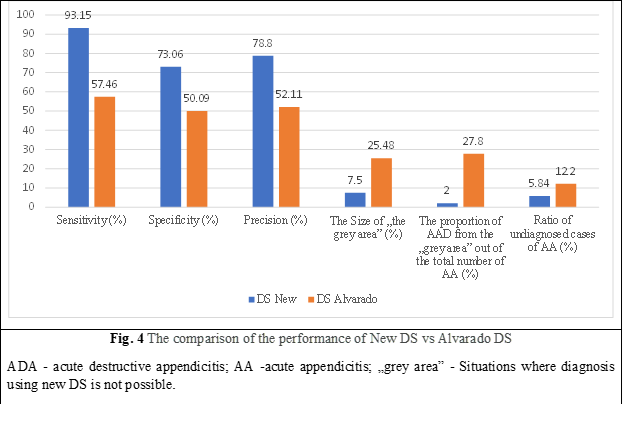

As a result of the comparative evaluation of New DS and Alvarado DS, it was observed that New DS has significantly higher sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy, and the number of undiagnosed AA cases compared to Alvarado DS is lower. If Alvarado's AA DS had been used in undiagnosed AA cases, there would have been 1.6% perforated, gangrenous, and complicated AA.

The size of the „grey area” and the weight of the „grey area” of AA, out of the total number of AA in New DS, was significantly smaller than in DS Alvarado (p < 0.001). The comparative evaluation of the main performance indicators New DS and DS Alvarado is shown in Fig. 4.

Thus, New DS showed greater clinical effectiveness in diagnosing AA in the elderly compared to the non-standardized clinical method and DS Alvarado, a lack of dependence on „risk factors” for diagnosing AA, such as obesity and atypical location of VA.

Discussion

This study evaluated the acceptability of the Alvarado scores and the developed New DS in determining the diagnosis of AA in elderly patients.

Early diagnosis of AA is quite laborious in elderly people, having a high mortality and morbidity rate. In a study conducted in Finland, the data of 164,579 patients who underwent appendectomy surgery were examined over a 20-year period, and mortality increased 39 times in patients over 60 years. Similarly, the same study determined that negative appendectomy increased four-fold and mortality increased 10-fold. In the literature, the rate of negative appendectomy in geriatric patients ranges from 17% to 31% [3-4]. In the current cohort, the negative appendectomy rate was 28.3%, which is in accordance with the specialized literature.

Due to increasing life expectancy, diseases previously associated with the younger population, including AA, have an increasing incidence among elderly patients [6]. Although the lifetime risk of AA is 7% for the general population, this rate may increase to 10% among the elderly population [2]. As in most diseases, the clinical diagnostic process of AA is more difficult in the geriatric population than in the young. This is due, in part, to altered pain sensations due to impaired nerve conduction as a result of aging and the atypical picture of classical AA [6]. Since a delayed diagnosis will increase the mortality and morbidity of AA, international guidelines and evidence-based medicine guidelins recommend the use of clinical scoring systems in the initial evaluation process of patients [15].

The Alvarado score [17-19] being a 10-point scale based on indications, symptoms, and laboratory data, is one of the most widely used and evaluated scoring systems for the assessment of AA. A score of 5 or 6 points on the Alvarado scale is considered compatible with the diagnosis of AA; a score of 7 or 8 suggests a plausible diagnosis of AA; and a score of 9 or 10 indicates a very likely diagnosis of AA. This diagnostic score was designed to assist clinicians in clinical decision-making by objectively determining which patients should be monitored and evaluated and which should be operated on. The limited research that assessed the relevance of the Alvarado score in the elderly population, retrospectively analyzing 96 patients over 60 years of age, using the Alvarado score system with a cut-off value of 5, demonstrated high efficacy in the elderly [17]. In another study, the Alvarado and Lintula scores were compared in elderly patients undergoing appendectomy, and the former was found to be a more useful predictive tool, with an AUC value of 96.9% [18]. Another research, however, demonstrated that the Alvarado score is ineffective in elderly people [5].

There are, however, some limitations to our study. First, the results obtained by us cannot be generalized to the general population, since they were obtained from a single center. Second, because this study was retrospective, the results may have been influenced by inadequate or erroneous data from hospital records. Another disadvantage is the small group of patients.

Conclusions

The use of the diagnostic score in the elderly will raise the quality of care, reduce the amount of time it takes to diagnose a similar case and as a result - lead to a reduction in complications and mortality in acute appendicitis. The study of the efficacy of new AA DS by comparative evaluation with the traditional non-standardized clinical diagnosis of AA and Alvarado AA DS demonstrated higher clinical efficiency in diagnosing AA with sensitivity up to 93.15% compared to the non-standardized clinical method and Alvarado AA DS and also does not depend on „risk factors” for AA diagnoses such as obesity and atypical location of AV, due to which we recommend wide application in medical practice.

Competing interests

None declared.

Patient consent

Obtained

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Nicolae Testemițanu State University of Medicine and Pharmacy (Minutes No. 25, from 21.11.2016).

Author’s ORCID ID

Alexandr Gaitur – https://orcid.org/0009-0005-0512-7515

References

Ceresoli M, Zucchi A, Allievi N, Harbi A, Pisano M, Montori G, Heyer A, Nita GE, Ansaloni L, Coccolini F. Acute appendicitis: epidemiology, treatment and outcomes- analysis of 16544 consecutive cases. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8(10):693-699. doi: 10.4240/wjgs. v8.i10.693.

Kraemer M, Franke C, Ohmann C, Yang Q; Acute Abdominal Pain Study Group. Acute appendicitis in late adulthood: incidence, presentation, and outcome. Results of a prospective multicenter acute abdominal pain study and a review of the literature. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2000 Nov;385(7):470-481. doi: 10.1007/s004230000165.

Kotaluoto S, Ukkonen M, Pauniaho SL, Helminen M, Sand J, Rantanen T. Mortality related to appendectomy; a population based analysis over two decades in Finland. World J Surg. 2017;41(1):64-69. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3688-6.

Franz MG, Norman J, Fabri PJ. Increased morbidity of appendicitis with advancing age. Am Surg. 1995;61(1):40-44.

Shchatsko A, Brown R, Reid T, Adams S, Alger A, Charles A. The utility of the Alvarado score in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in the elderly. Am Surg. 2017;83(7):793-798.

Lau WY, Fan ST, Yiu TF, Chu KW, Lee JM. Acute appendicitis in the elderly. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1985;161(2):157-160.

Pokharel N, Sapkota P, Kc B, Rimal S, Thapa S, Shakya R. Acute appendicitis in elderly patients: a challenge for surgeons. Nepal Med Coll J. 2011;13(4):285-288.

Horattas MC, Guyton DP, Wu D. A reappraisal of appendicitis in the elderly. Am J Surg. 1990;160(3):291-293. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(06)80026-7.

Körner H, Söndenaa K, Söreide JA, Andersen E, Nysted A, Lende TH, Kjellevold KH. Incidence of acute nonperforated and perforated appendicitis: age-specific and sex-specific analysis. World J Surg. 1997;21(3):313-317. doi: 10.1007/s002689900235.

Zbierska K, Kenig J, Lasek A, Rubinkiewicz M, Wałęga P. Differences in the clinical course of acute appendicitis in the elderly in comparison to younger population. Pol Przegl Chir. 2016;88(3):142-146. doi: 10.1515/pjs-2016-0042.

Lunca S, Bouras G, Romedea NS. Acute appendicitis in the elderly patient: diagnostic problems, prognostic factors and outcomes. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2004;13(4):299-303.

Bhullar JS, Chaudhary S, Cozacov Y, Lopez P, Mittal VK. Acute appendicitis in the elderly: diagnosis and management still a challenge. Am Surg. 2014 Nov;80(11):E295-E297.

Segev L, Keidar A, Schrier I, Rayman S, Wasserberg N, Sadot E. Acute appendicitis in the elderly in the twenty-first century. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19(4):730-735. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2716-9.

Sülberg D, Chromik AM, Kersting S, Meurer K, Tannapfel A, Uhl W, Mittelkötter U. Altersappendizitis [Appendicitis in the elderly]. Chirurg. 2009;80(7):608-614. doi: 10.1007/s00104-009-1754-4. German.

Fugazzola P, Ceresoli M, Agnoletti V, Agresta F, Amato B, Carcoforo P, The SIFIPAC/WSES/SICG/SIMEU guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis in the elderly (2019 edition). World J Emerg Surg. 2020 Mar 10;15(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s13017-020-00298-0.

Blomqvist PG, Andersson RE, Granath F, Lambe MP, Ekbom AR. Mortality after appendectomy in Sweden, 1987-1996. Ann Surg. 2001;233(4):455-460. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200104000-00001.

Ohle R, O'Reilly F, O'Brien KK, Fahey T, Dimitrov BD. The Alvarado score for predicting acute appendicitis: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2011;9:139. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-139.

Di Saverio S, Birindelli A, Kelly MD, Catena F, Weber DG, Sartelli M, et al. WSES Jerusalem guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2016 Jul 18;11:34. doi: 10.1186/s13017-016-0090-5.

Alvarado A. A practical score for the early diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15(5):557-564. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(86)80993-3.

Harbrecht BG, Franklin GA, Miller FB, Smith JW, Richardson JD. Acute appendicitis - not just for the young. Am J Surg. 2011;202(3):286-290. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.08.017.

Krajewski S, Brown J, Phang PT, Raval M, Brown CJ. Impact of computed tomography of the abdomen on clinical outcomes in patients with acute right lower quadrant pain: a meta-analysis. Can J Surg. 2011;54(1):43-53. doi: 10.1503/cjs.023509.

Terasawa T, Blackmore CC, Bent S, Kohlwes RJ. Systematic review: computed tomography and ultrasonography to detect acute appendicitis in adults and adolescents. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(7):537-546. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-7-200410050-00011.

Doria AS, Moineddin R, Kellenberger CJ, Epelman M, Beyene J, Schuh S, Babyn PS, Dick PT. US or CT for diagnosis of appendicitis in children and adults? A meta-analysis. Radiology. 2006;241(1):83-94. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2411050913.

Marudanayagam R, Williams GT, Rees BI. Review of the pathological results of 2660 appendicectomy specimens. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41(8):745-749. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1855-5.

Pooler BD, Lawrence EM, Pickhardt PJ. MDCT for suspected appendicitis in the elderly: diagnostic performance and patient outcome. Emerg Radiol. 2011;19(1):27-33. doi: 10.1007/s10140-011-1002-3.

Barreto SG, Travers E, Thomas T, Mackillop C, Tiong L, Lorimer M, Williams R. Acute perforated appendicitis: an analysis of risk factors to guide surgical decision making. Indian J Med Sci. 2010;64(2):58-65. doi: 10.4103/0019-5359.94401.

Gürleyik G, Gürleyik E. Age-related clinical features in older patients with acute appendicitis. Eur J Emerg Med. 2003;10(3):200-203. doi: 10.1097/00063110-200309000-00008.

Konan A, Hayran M, Kılıç YA, Karakoç D, Kaynaroğlu V. Scoring systems in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in the elderly. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2011;17(5):396-400. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2011.03780.

Agafonoff S, Hawke I, Khadra M, Munnings V, Notaras L, Wadhwa S, Burton R. The influence of age and gender on normal appendicectomy rates. Aust N Z J Surg. 1987;57(11):843-846. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1987.tb01277.x.

Rub R, Margel D, Soffer D, Kluger Y. Appendicitis in the elderly: what has changed? Isr Med Assoc J. 2000;2(3):220-223.